Albert Pinkham Ryder

Albert Pinkham Ryder: The Race Track

Inspired by an event at the Hotel Albert

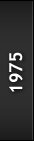

The details of Ryder’s connection to the Hotel Albert are not entirely clear. Some relatively recent accounts have claimed that his brother built the hotel and named it for him. In fact, the hotel was built by Albert S. Rosenbaum, who most likely named it for himself, but Ryder’s brother did indeed manage the Albert for Rosenbaum, and had been the owner and manager of the adjoining St. Stephen’s Hotel since 1876.

In his 1898 obituary, the New York Times described William Ryder as follows:

The death of William Davis Ryder, who was for nearly twenty years the proprietor of the Hotel St. Stephen, in Eleventh Street near University Place, occurred at 7 o’clock Wednesday evening at his home, 16 East Twelfth Street. A few years ago his health broke down, but he managed to recuperate. Last October an attack of kidney trouble forced him again to take to his bed, which he never afterward left.

Mr. Ryder was born in January, 1837, at Yarmouth Port, Mass., and not long afterward he went with his parents to New Bedford, Mass., where he was reared and educated. At the outbreak of the war of the rebellion Mr. Ryder, with J.L. Jones, then both in business in Boston, joined the Army of the Potomac, in partnership as sutiers [sic] remaining with the army through the war. They then came to this city together and opened, at Broadway and Howard Street, a. restaurant under the firm name of Jones & Ryder. This restaurant, which was at that time the largest in the city, and much patronized by prominent New Yorkers, lasted till 1876, when the partners left it and purchased the Hotel St. Stephen. A year or two later Mr. Ryder bought out Mr. Jones’s interest in the hostelry and continued to run it alone until about three years ago, when he sold it and retired from business. He also opened the Hotel Albert and managed that for its owner. The Pacific Bank is another institution in which Mr. Ryder was interested financially. He married Miss Albertine Burt of New Bedford, Mass. She survives him, as does a daughter, Miss Gertrude H. Ryder. Mr. Ryder belonged to the Hotel Men’s Association. He will be buried at New Bedford, Mass., to-morrow.

One contemporary account, by a reporter seeking unsuccessfully to interview Albert Ryder, suggests that the painter lived at the Hotel Albert at some point:

Upon consulting my diary for March 11, 1911, I find the following staccatic references to my ineffectual attempts to meet [Albert] Ryder....

“Ryder was charmed at the idea of meeting a friend of Mr. Fearon’s, but wished a few days in which to arrange for it. Mr. Fearon explained that the artist lived in great disorder, and probably wished to fix up his room a bit. Two days later a messenger reported that Ryder was no longer at home. ‘Probably ambling around the country roads in New Jersey,’ explained Mr. Fearon, ‘taking advantage of the springlike weather.’ Two days later than that the messenger reported finding Ryder at home, but the room appalling. Floor piled high with ashes and all kinds of debris. ‘You know more than once,’ said Mr. Fearon, ‘the Board of Health has got after him. Once when Ryder was ill the Reillys, who live on the floor below, managed to get in and gave the place a thoroughly good housecleaning, but that is the only such event on record.’

“Last Saturday Ryder called on Fearon and said that he would appoint a day soon for the interview. Mr. King said last night that he had called once on Ryder and Ryder had given him one of his rooms. ‘You know his brother owns the Hotel Albert. He named the hotel after Ryder.’

“Called at the Hotel Albert to-day. Mr. Ryder not at home. Clerk said Mr. Ryder was a traveling salesman. Didn’t think he had ever owned that hotel. A Mr. Rosenbaum had owned the Hotel Albert for years.”

I think it was Ernest Lawson who finally put me au courant, told me the sort Ryder was, the simplicity of his character and the style of life. As soon as I learned the facts I gave up the idea of an article, as I did not wish to assist in starting a pilgrimage of busybodies and idlers to the retreat of the aged and picturesque painter...

Ryder took his meals at the Hotel Albert, and it was an episode at the restaurant that inspired one of his most famous paintings, “The Race Track.” In Ryder’s own words (which suggest that his brother ran the hotel but that Ryder himself did not live there at the time – but since Ryder refers only to “my brother’s hotel,” it could conceivably have been the St. Stephen):

In the month of May, the Brooklyn Handicap was run, and the Dwyer brothers had entered their celebrated horse Hanover to win the race. The day before the race I dropped into my brother’s hotel and had a little chat with this waiter, and he told me that he had saved up $500 and that he had placed every penny of it on Hanover winning this race. The next day the race was run, and, as racegoers will probably remember, Hanover came in third. I was immediately reminded that my friend the waiter had lost all his money. That dwelt in my mind, as for some reason it impressed me very much, so much so that I went around to my brother’s hotel for breakfast the next morning and was shocked to find my waiter friend had shot himself the evening before. This fact formed a cloud over my mind that I could not throw off, and “The Race Track” is the result.

In 1928, the Cleveland Museum of Art, which had acquired the painting, published an article about it in the museum’s Bulletin,iii elaborating on the story:

In his most famous canvas, “The Race Track,” better called “Death on a Pale Horse,” recently added to the J. H. Wade Collection, Albert Pinkham Ryder deals with the eternal problem of death, not in any mood of morbid curiosity, but instead with an inevitability which has in it the character of the subject matter itself….

The actual experience which called forth this picture has been described by Ryder himself in a short account of some three hundred words, almost the only bit of sustained writing which he ever attempted. His brother was the proprietor of a small hotel in New York, the Hotel Albert. The artist was accustomed to take his dinners there, and many times he was served by a waiter who attracted him by his unusual competence and intelligence. This waiter was interested in horse racing, and mentioned one time that betting on the races was an easy way to make money; Ryder advised against it. Later he heard that the man had bet his entire savings, five hundred dollars, on the horse, Hanover, entered in the Brooklyn Handicap, a horse then much talked about from the Dwyer brothers’ stables. The morning after the race, Ryder read of the result: Hanover had come in third. He was overcome with immediate forebodings, and went around to his brother’s hotel to find that the waiter had shot himself the night before. The whole affair moved him immensely; and this painting, “Death on a Pale Horse,” is a direct result of his emotional excitement. It is a commentary too on his point of view. Shocked as he was by the tragedy, in his intelligence he was not so wholly concerned with the event itself as with the circling reflections which it aroused.

The canvas, in accordance with Ryder’s mood, is one of highly romantic and expressionistic character. Around the track rides Death, a phantom figure upon a phantom horse. Every line gives speed; and the opposing rhythm of the scythe, as it repeats the line of the curving edge of the track, suggests the relentless returning of the course upon itself. These lines give an effect of immensity as well, accentuated by the depths of a ghost-like evening sky, its livid clouds outlined against weird patches of deep blue. A blasted tree, stripped of branches and foliage, stands starkly at one side; and from a stagnant pool in the foreground glides a serpent, “that which runneth quicker than death itself.” Mysterious shadows fall here and there over the canvas, and the greyed and brownish greens of the color scheme give an effect that is at the same time haunting and poignant.

Ryder lived in a world apart; he was a recluse, a mystic, content to exist in a tiny studio amid inextricable disorder. It did not matter to him whether the room was filled with a number less accumulation of boxes of Quaker Oats or other things; that was only where his body stayed while his mind ranged through endless spaces of imagination. He might take a simple idea; but when he was through with it, he had left it enriched with a fullness of reflection which makes of it a profound philosophy. That is why Ryder stands in his chosen field as the greatest American Romanticist; and that is why the newly acquired can vas, “Death on a Pale Horse,” can be fairly called, without exaggeration, one of the greatest canvases ever painted in America.